“My films aren’t really shown in Pakistan,” laughs the country’s greatest living – and most radical – film director, who now lives in a converted chapel in Camden, north London. “They’re a bit too risque.”

To catch a Jamil Dehlavi film in his homeland is tricky. The last time was in 2006, when Infinite Justice, his docudrama about an American reporter held hostage and beheaded in Karachi, was shown somewhere on the Arabian seafront, the same Karachi shore you see in his films, shaded by the heaviness of monsoon clouds, the beige pallor of the light, and the tracks of sea turtles laying their eggs along the sand.

Born in the twilight of the partition, in 1944, to a Pakistani diplomat father and a French mother, Dehlavi was educated at Oxford University and called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn – which he abandoned in favour of studying film at Columbia University in New York. Over the decades, Dehlavi has captured the dark quality of Pakistan’s existential turbulence: its chaos, controversies and longings.

His breakthrough was 1980’s The Blood of Hussain, an insurrectionary drama that earned the young film-maker his laurels as a creative troublemaker. Dedicated to “the people of Pakistan”, it is the tale of Saleem and Hussain, two brothers from a feudal family. The anglicised Saleem signs on to help negotiate World Bank loans for a new military government; Hussain lives on the land and devotes his life to protecting the poor from the oppression and greed of the country’s military elite.

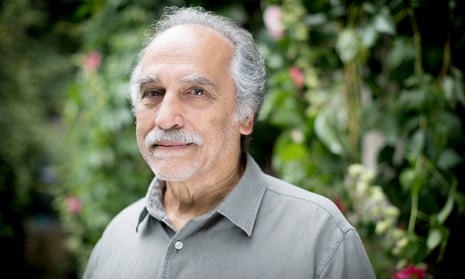

One month after shooting finished, Gen Zia ul-Haq toppled Pakistan’s elected government and declared martial law. The film was banned and Dehlavi forced to flee the country. “Did I predict the military coup?” he smiles, unweathered by time at 73. “I’m not a fortune-teller. In Pakistan, there is always something in the offing.”

The film was more than just prescient, it was dangerously transgressive. A moustachioed dictator shoots doves for sport. Soldiers beat peasants and bulldoze houses. A street entertainer dresses a monkey in uniform and congratulates him for becoming president before translating his babbles: “He says democracy is dead and you’re in real trouble.”

Today, the media wing of Pakistan’s military are successful producers of commercial propaganda films such as Waar and Glorious Resolve. But The Blood of Hussain belongs to a different era, one when no artist would do the state’s bidding. Yet Dehlavi stresses that he never saw it as an anti-army film. It was rather, he says gently, “an abstract essay on tyranny”.

That film began with Zia’s coup. His next, Immaculate Conception, was released in 1992, in the aftermath of the dictator’s death. Emboldened, Dehlavi sought out a new taboo: sex. An infertile western couple submit themselves to a Karachi shrine run by transgender hijras, who promise that converting to Islam will bring them the miracle of a child.

This sensitive desi Rumpelstiltskin fable attacks white privilege, fetishisation and power, while taking care not to debase the people at the heart of the story. When a British do-gooder asks if he can photograph the hijras, the young woman replies: “Sure, you can take pictures, but don’t degrade us. We may be eunuchs, but we have our dignity.”

Dehlavi’s films reflect Pakistan. They have messy, non-linear and humorous narratives that make sense in an environment of multiplicity and disorder. But even by his surreal standards, the director took an odd turn with 1998’s Jinnah, which starts with Christopher Lee, as the founder of Pakistan, arriving in heaven to find that his file has been lost. An angel – Shashi Kapoor in a voluminous white salwar kameez – suggests that, since the computer isn’t working, they can just walk around for one and a half hours playing 20 questions instead. Would you do it again, he asks, referring to the creation of the country? What did you think of Gandhi? Were you ever jealous of Nehru?

No, Jinnah huffs in response to the last, while the film launches a series of sleazy cheap-shots against his adversaries including, but not limited to, mutilating their names every time they are mentioned. It gets worse – but it could, it turns out, have been considerably weirder.

“There was a whole other strand that we didn’t shoot,” Dehlavi says, “in which Jinnah time travels and meets modern Muslim leaders like Saddam Hussain, Yasser Arafat and Muammar Gaddafi. But three-quarters of the way through the shoot, the Pakistani government pulled out of the film.”

Even before state support was withdrawn, Jinnah was mired in stress and controversy. Campaigns accused the film of denigrating the father of the country by casting Dracula to play him and suggested that Salman Rushdie had written the script (he had nothing to do with it). At the height of the Rushdie rumours, armed bodyguards had to be stationed outside the actors’ Karachi hotel. “I was approached to make the film,” Dehlavi says. “I’m not sure it’s a film I would have initiated.” He trails off.

His more recent work grapples with real horror, rather than the hallucinatory. Infinite Justice, based loosely on the murdered journalist Daniel Pearl, was born out of Dehlavi’s reaction to 9/11. “I was downstairs and the television was on in the background,” he says, “and suddenly these images of the twin towers and the planes hitting them came on. When I saw this, I said out loud to my friend: ‘Serves them right.’” He pauses as the words hang in the air. “And I wondered, why did I feel this way?”

Dehlavi’s guerrilla film-making comes from this impetus – to question both external terror and the shock of our response. His brother once told him that he was always taking on the government and, in some way, his cinematic interventions (Jinnah aside) have picked at sacred cows. Seven Lucky Gods (the Chinese figurines from the film’s title sit behind Dehlavi today, displayed in an elegant armoire) interrogated migration and the power and abuse of a British politician, while Blood Money, a 2016 short, is a revenge fantasy loosely based on Raymond Davis, the CIA contractor who shot two innocent men in Lahore and was spared jail by Pakistan. All follow the same disobedient impulse: to question the unquestionable.

For a generation of Pakistanis born in the shadows between martial law and censorious civilian governments, Dehlavi’s early films are especially evocative because of their audacity. We met in the weeks before Pakistan’s recent elections, which were blighted by suicide blasts, political tension and claims of widespread army interference, but studiously avoided the topic. In these uncertain times, commentary comes at a price.

I wonder what Dehlavi makes of the films coming out of Pakistan today and he offers some bland encouragement: he hopes they are successful, though he’s not sure what the industry’s trajectory will be. Does he see anyone on the horizon making “abstract essays on tyranny”? “No,” he shakes his head solemnly, “and there won’t be any because we have a repressive system, we have a censor board that’s strict.”

Would he return to films that take on Pakistan’s shadowy powers? “I doubt it. I don’t think one can mess with the military these days.” Dehlavi tells me he is working on a new script: a gangster film set in the Karachi underworld. He wants to shoot it in Urdu on location in Machar Colony, the city’s largest slum, with a cast of local actors. Is that safe? I ask. “Why wouldn’t it be?” he replies, still smiling.

Between the Sacred and the Profane: The Cinema of Jamil Dehlavi is at the BFI Southbank, London, from 10-12 August, with Dehlavi in conversation on 11 August. The Blood of Hussain and Towers of Silence will be released on Blu-ray and DVD on 22 October.

Fatima Bhutto is the author of The Shadow Of The Crescent Moon and the forthcoming novel The Runaways (Viking, March 2019).