It is a wet and blustery August morning: perfect Michael Caine weather. When the actor returned to Britain in the 1980s after a decade in Los Angeles, he claimed it was because he missed the rain, although there was also the happy coincidence that the Conservative government (“Maggie,” he says, with inextinguishable fondness) had implemented a tax structure more favourable to those on extravagant incomes. Of which more, inevitably, later: a conversation about tax is the price you pay for the considerable pleasure of Caine’s company.

On the day we meet, it is half a century almost to the month since Caine (who wasn’t a “Sir” until 2000) laid out his career plans in the Daily Express.

“Go on,” he says, beaming in anticipation as I hold the newspaper cutting before me and read back to him his own words from October 1968. “I will carry on with this life until I am 45 and then move out to a farmhouse, fill it with kids and grow old gracefully. Forty-five is a good age to retire from the hunt.”

He tips his head back, releasing that infectiously jolly heh-heh-heh that provided a permanent soundtrack to talkshows in the 1970s and 80s. But just imagine if he had thrown in the towel at 45. His career would have been over in 1978, which means his swansong could very well have been The Swarm, that killer-bees thriller routinely cited – alongside stiff competition from Jaws: The Revenge – as the worst film among the 100-plus titles on his CV. At the time, he blamed the bees: “I always knew they couldn’t act,” he said, displaying that endearing knack he has for shrugging off disaster. (“I enjoy the television shows where they select the year’s best and worst films,” he once said. “I’m always on both lists.”)

Retiring in 1978 would have meant sacrificing some of his finest work: no Dressed to Kill, no Educating Rita, no Hannah and Her Sisters (the film which won him the first of two Oscars to date; The Cider House Rules brought the second). Goodbye to his debonair conman in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and to his six films with Christopher Nolan (seven if you count his uncredited voice cameo in Dunkirk). And who would want to live in a world without Caine jigging through the streets in his dressing gown as Scrooge in The Muppet Christmas Carol? Not me.

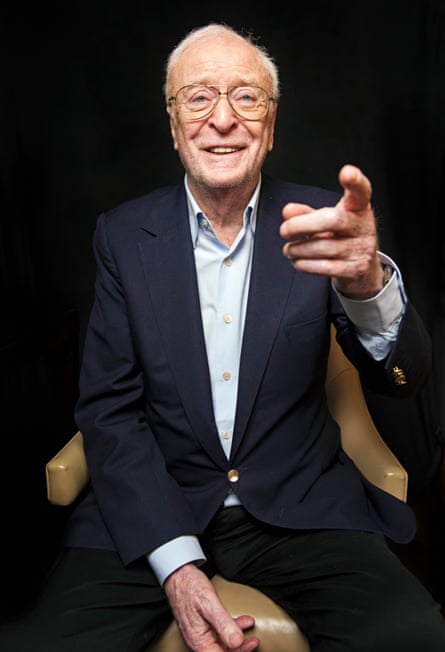

And now, here he is at 85 years old, in a dark suit and duck-egg-blue shirt, feet up on the chaise longue to rest the ankle he broke earlier this year when he fell over in his garden. A wooden stick lies next to him. “I don’t need it at home where there’s carpet,” he explains, giving it a tap. “But I don’t want to fall over in Regent Street, you know?”

What happened to the big retirement plan: where did it all go wrong?

“What happened is I enjoy it so much that I just can’t stop,” he says, watery eyes twinkling behind his specs. “Things go up and down and you do what comes along. You have to make a living. What I noticed looking back was there’d always be three or four flops and then just as it was all going in the toilet, there’d be a hit, a massive hit. So I feel very lucky.” He’s shooting a film next month in the Czech Republic (“The director said I can keep the stick for the part,” he says cheerfully) and there is already another project lined up for next year. “They’re not leads. I don’t want the bloody lead any more.”

That claim is contradicted by the film which has occasioned our meeting: King of Thieves, a dramatisation of the 2015 Hatton Garden robbery, in which more than £200m-worth of cash, jewellery and other valuables was stolen from a vault of safe deposit boxes by six old pros with a combined age of about 440. Caine plays the ringleader, the 77-year-old widower Brian Reader, and the rest of the cast is a turkey-necked, arthritic dream: Tom Courtenay, Michael Gambon and Jim Broadbent, with Ray Winstone a mere stripling at 61. The picture starts out light and larky before taking a welcome swerve into nastiness as these supposedly lovable codgers with their insulin injections and their corned-beef sandwiches begin to show their true colours. To see Caine viciously berating Gambon is to savour that particular clammy malice which he demonstrated in films such as Get Carter, Mona Lisa and Blood and Wine.

“They left the ‘cunt’ in, then?” Caine asks when I mention the scene with Gambon. “I asked them to cut it.”

Why? “I don’t know,” he says softly, staring at his lap.

It is an important moment, I insist, since it shows how vicious these men can be. “Oh, they were nasty pieces of work,” he agrees. “They all had records. But there was something funny about them, too.” Several films have been made about the robbery, but Caine signed up early on to the one produced by Working Title and drawn from reporting by Duncan Campbell for this newspaper. (“I thought whoever gets Michael Caine to do it is probably going to win this race,” the producer Tim Bevan has said.)

Caine claims that police would not allow him to meet the real Reader, who was released last month. “But sometimes things that seem bad at first turn out to be handy. When Brian’s daughter discovered I was playing her dad, she said: ‘He’s too common.’ Now, that gave me a clue as to how he would speak. I knew he was a cockney but he’d married a woman from Dulwich and they lived in Blackheath, both of which are posh, so I thought he might’ve improved his accent, which I’ve done, too. No one would have a clue what I was on about otherwise. Do you know I did 120 loops of Alfie cos the Americans couldn’t understand what the fuck I was saying?”

The film doesn’t go in for trivialising crime and nor does Caine, who grew up in criminal company around Elephant and Castle in south London. “I was a gentle soul, but some of my friends went out and smashed people up. I only knew one murderer. I based my character in Get Carter on him: the way he moved, everything. He’d killed four people, never been caught. After Get Carter came out, he said: ‘Biggest load of crap I’ve seen in my life.’ I asked him why. He said: ‘You’re not fucking married. We had responsibilities. That’s why we did what we did. Why are you doing it? Where’s your responsibilities?’ Isn’t that amazing? I didn’t argue with him: I knew he’d killed four people. And if I’m gonna get killed, I wanna be number one.” There comes that laugh again.

He has his own theories about crime today. “For a start, there’s not enough police. You always saw a bobby on the beat when I was growing up. And socially, I think there’s something badly wrong because a lot of the killings are coloured boys killing other coloured boys.” I wince slightly, and he leans in as if to reassure me: “I don’t say that with prejudice. It’s just that you have to go back deeper, farther back socially, to where it starts. They can’t get a job so they start thieving, riding around on bikes stealing watches. You know? I come from that background myself so I know about it. I did a movie called Harry Brown and we filmed on an estate in the Elephant and Castle where my aunt used to live. All these young men came on the set and started talking to me and they were all black, all of em, and they were just the same as us, as our lot, a load of ruffians. Some of em nicking. They’re trying to make money. That’s all they’re trying to do.”

I have the peculiar sensation not of having given Caine too much rope but of perhaps needing to confiscate the rope from him while we focus instead on working out what it is he is saying. Does he mean that crime comes from poverty, irrespective of race?

“It comes from poverty, yes. But the people who are suffering that poverty, it seems, are darker people, shall we say.”

Is he trying to identify the part played in poverty by prejudice?

“It comes from prejudice, yes, and they grow up with it, you know? I’ve seen it a lot, I spent a lot of time on Harry Brown with these boys, talking to them, and there was no fear on my part, no threat to me even though I was white. I was one of them – an older one of them. I come from that background and I know exactly what it’s like, and it has to be looked at socially.”

Having lived in the US, how does he see Donald Trump handling that country’s particular schisms?

“I know him quite well,” he says. “We went to dinner. He made me laugh.” Then he corrects himself: “I don’t know him very well and I feel I know him less now than when I knew him a little bit. When someone said he was running for president, I said: ‘President of what? Marks & Spencer?’ I’m sure he was quite surprised himself to become president. On one hand, he’s a danger and unpopular. But suddenly he’s become very successful: the stock markets are up, and employment, including the Spanish and blacks. The figures are starting to be on his side, so you wonder, you know, what the hell is going on? The point is that his people, they’ve never been represented politically and they are a majority. It’s very strange.”

Would Caine have voted for him? “No, no. I’m a Democrat, I’m afraid.”

And yet a Tory at home. “Well, I’m a very leftwing Tory. I’ll give you an example: taxing the rich. You mustn’t tax them so much that they leave, because then you’re gonna get what’s called ‘nothing’. Now, I’ve paid millions in tax in this country …” What follows is a disquisition on the subject of how to make Britain attractive for the wealthy, concluding with the announcement: “If we end up with Corbyn, everyone will leave.”

Caine is still as rabidly pro-Brexit as he ever was, despite experts warning of a no-deal Brexit marked by everything from food shortages and civil unrest to breakdowns in anti-terrorist intelligence. “I’ve said it before: I’d rather be a poor master than a rich servant. What I see is I’m being ruled by people I don’t know, who no one elected, and I think of that as fascist, you know?”

But what of the real fascists, I ask him, those far-right politicians making significant gains across a fractured Europe. Isn’t he worried about them?

“Europe was OK before,” he says. “It’s been there for thousands of years.” He returns abruptly to his previous point: “I can’t believe that someone we don’t know who wasn’t elected is telling us what to do. And it’s just, you know. I, I … My dad fought against Nazism, I fought against communism in Korea. And we seem to be doing all right on our own. They said: ‘When the empire goes, you’re gonna be …’ Well, we seem to be doing all right now.” He attributes the current panic over a no-deal Brexit to scare tactics. “That’s all. Cos Europe will lose financially. We will, too. It’s gonna be a disaster for all of us. In the long run, though, it’ll come round.”

To get us back onto the topic of cinema, I ask a few quickfire questions about some of the things he hasn’t done: he never made a western, for instance. “I hate horses. Or rather, I like them but they don’t like me.” And unlike friends and contemporaries such as David Hemmings, Jack Nicholson and Caine’s old flatmate Terence Stamp (with whom he once wrote a screenplay called Over the River: “We lost it and I can’t remember what it was about”), he steered clear of the European arthouse until very recently, when he played a retired composer in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth. “Nobody ever asked me before,” he says. “A lot of actors make these great films for great directors while Michael Caine here is making a load of shit. But while you’re sitting there waiting for the great man to call with a great part, you find you haven’t worked for two years.”

I ask what he thinks of the recent appointment by Vladimir Putin of Steven Seagal (with whom Caine starred in On Deadly Ground) as Russia’s special envoy for humanitarian ties with the US. “If you don’t do what he says, he’ll beat you up,” Caine laughs. For a second I’m not sure if he means Seagal or Putin. Then he says: “I think somewhere in Putin there’s a peaceful man.” The annexation of Crimea, and Putin’s virulently anti-LGBT laws, would suggest otherwise – and that’s just for starters. So I ask Caine what evidence he has to support his claim. “I don’t know,” he says. “I just watch him and listen to him. I spend a lot of time looking at Putin. Somewhere there’s a good side and we haven’t found it.”

He smiles warmly, shrugging off disaster yet again, and treating the Russian president as though he’s another dodgy film destined for the bargain bin.