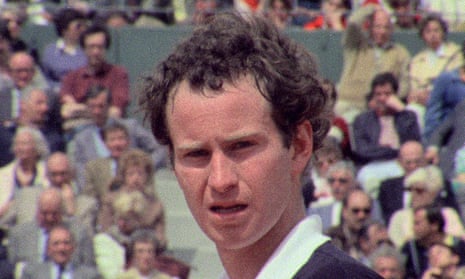

John Patrick McEnroe was the wayward artist of men’s tennis, a spoilt-brat genius who used his racket as a wand. Throughout his peak year of 1984 he conjured magical winners from impossible angles and whipped furious storms from the calmest of waters. His matches became a box office draw – high-octane drama beamed live to the masses.

I first fell for tennis during McEnroe’s mid-80s heyday, at about the same time I fell in love with cinema. So I am indebted to the director Julien Faraut for reconciling my twin passions. Tennis, he insists, is the most cinematic of sports. Its top-flight athletes are the equivalent of movie auteurs. These players are distinctive, inimitable and in perfect command of their material. That is, until the moment they’re not.

Faraut’s film – John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection – is a playful low-budget documentary, pieced together from found footage, scrutinising the man’s ill-fated dash towards the 1984 French Open title. Vogue magazine calls it “the greatest tennis film ever made”, which may be a case of big fish, small pond. But it’s certainly an illuminating and unusual tight-focus study of the player.

Faraut, it turns out, works as an audio-visual archivist at France’s National Institute of Sport. One day, he uncovered old reels of 16mm film, shot courtside by a man called Gil de Kermadec, the one-time technical director of the French Tennis Federation. De Kermadec’s closeup footage captured McEnroe’s volcanic rages at the umpire and the uncoiling whip of his stinging left serve. Faraut was entranced: “When you look back at old tennis matches, it’s always poor-quality video. Always the same boring edits, the same boring angles. But this felt dramatic, grainy, cinematic. When you focus on one man, it creates a kind of empathy.”

The film’s style feels novel; in fact it is as old as the hills. Faraut says that sport has always been part of cinema’s DNA and that Thomas Edison’s first kinetoscope films were actually tight-focus studies of boxers in the ring. He might also have cited Leni Riefenstahl’s notorious Olympia, which conjured its divers into gorgeous abstracts, like Matisse’s late cutouts, or the 2006 film Zidane: A 21st-Century Portrait, which close-marked the footballer through the course of one match. The most interesting sports movies, perhaps, are the ones that are confident enough in their material to frame the technique and avoid trying to cover all the bases. They’re beautifully simple; more poetry than prose.

That being said, there’s a thesis here as well. Fittingly for a film that opens with a quote from Jean-Luc Godard (“Cinema lies, sport doesn’t”), In the Realm of Perfection is as much about film as it is about tennis, keen to cast the two disciplines as natural bedfellows. Tennis, it argues, bears a likeness to film in that the length of a match is flexible, elastic, defined by the contest and largely adhering to the running time of a feature. Moreover the best players are essentially actor-directors, at once participating in the drama and dictating it. To prove his point, Faraut intercuts McEnroe’s tantrums with clips from Raging Bull and reminds us that Tom Hulce based his performance in 1984’s Oscar-winning Amadeus on the American tennis star. “I’m a vulgar man,” Hulce’s Mozart concedes at one point. “But, I can assure you, my music is not.”

“Actually, I think McEnroe was more director than actor,” Faraut tells me. “That was the key misunderstanding between him and the public. They thought his tantrums were a performance, put on for show, and I don’t think that they were. If you don’t believe me, watch his TV commercials where he’s basically playing John McEnroe. He’s a really bad actor.”

The way Faraut sees it, McEnroe’s fiery outbursts were classic film-maker behaviour. Out on the court, he resembled a bullish director straining to realise his vision. “He wants to manage everything,” laughs Faraut. “He gives orders to everybody, even his opponents. He controls the space of the court like it’s the frame of a screen. He’s telling a story the way he wants it to be told.”

Of course, McEnroe lost that French Open final, squandering a two-sets-to-love lead to his closest rival, Ivan Lendl. Real life has a habit of breaking from the script. Not every good story comes with a happy ending.

Who knows why the genius went down to defeat? The afternoon heat may have played its part. Or perhaps a lean, hungry Lendl simply gained in strength, no longer content to play the role of second-best Salieri. But Faraut’s documentary suggests another tantalising possibility: that the catalyst for McEnroe’s meltdown was his anger at the whirring of the courtside cameras and the boom mic he felt was getting too close to his face. The moment McEnroe became aware of the film was also the moment he started to collapse, as if the machinery of movie production was in some way to blame.

“My life would have been completely different if I had won that match,” the world No 1 would later lament. But Faraut suspects it may have been the making of him. It gave his story some texture, ensured a lasting legacy. “It’s very hard to win everything,” Faraut says. “And art is not about achieving perfection. Losing that match showed McEnroe’s human dimension. He wasn’t a robot. He wasn’t a god. I see him as a superhero with a super weakness.”

I like that description. Faraut casts brattish John McEnroe as Jake LaMotta at the nightclub, or precocious Orson Welles, heading for a fall. The characters we remember are the ones with the flaws. The dramas we cherish are those that pitch towards disaster. That’s true of all cinema; it’s true of sport, too.

John McEnroe: In the Realm of Perfection is released on 24 May

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion