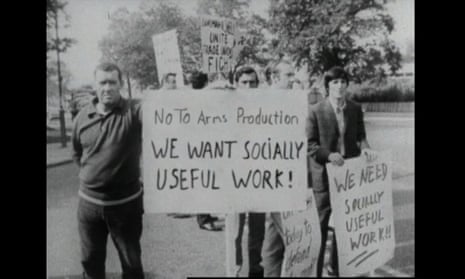

It was 1974. A new Labour government had come to power on the promise of defence cuts. Swingeing job losses were soon to follow. Desperate workers at one Birmingham factory – Lucas Aerospace – fought to save their livelihoods, not by downing tools but by transforming from weapons-makers into one of Britain’s first eco-manufacturers, with early designs for wind turbines and hybrid cars.

The extraordinary story of what became known as the “Lucas Plan” is now being told in a documentary, The Plan that Came from the Bottom Up, that screens for the first time this week at the BFI London film festival.

“It was a silent revolution, it took place inside the factories not on the streets. There weren’t the battles with the police that we saw with the miners and the dockers, it wasn’t dramatic like that,” said director Steve Sprung, who described what happened inside the Lucas factory as a “significant but forgotten” event in British political history. “But what these workers did was incredible,” he told the Observer.

Drawing on archive material and interviews with surviving workers, now in their 70s and 80s, the film juxtaposes present-day images of war and environmental damage, and asks what might have been if the “Lucas Plan” had ever seen the light of day.

“The workers realised they were on the brink of massive redundancies and were trying to save lives,” said Sprung, whose documentary charts their story in two parts over three-and-a-half hours.

The workers set up an unofficial trade union body, known as the Combine, to represent employees across the company’s 17 factories. They took their grievances to the then secretary of state for industry, Tony Benn.

“He told us that he couldn’t bail us out or include us in nationalisation,” said Phil Asquith, a research engineer at Lucas Aerospace at the time. “Instead, he told us to ‘plan what you would make instead of weapon systems’.”

The workers knew that this was their moment, Asquith says. They sought ideas from university academics on suitable alternatives to weapons. But after receiving scant replies, they turned instead to their own 18,000-strong workforce.

“We said, your jobs are under threat – if you don’t make weapons what else would you make? The response was patchy to begin with but then we got a torrent of ideas. It was amazing,” Asquith said.

They whittled down the suggestions to 150 products, each one deemed to be socially useful and environmentally friendly.

The ideas included drawings of wind turbines, energy-efficient heat pumps and hybrid power packs for cars – commonplace now but virtually unheard of in the 1970s.

“It was tough, and we argued, and sometimes there was almost blood on the floor, but what was coming through in terms of impact and support and ideas was truly exhilarating,” said Asquith.

The plan took on a powerful momentum of its own. What had started as a bid to stave off job losses turned into something with a much wider political and ethical agenda.

Mike Cooley, a Lucas engineer and member of the Combine, summed up the mood of the time: “It was an insult to our skill and intelligence that we could produce a Concorde but not enough paraffin heaters for all those old-age pensioners who die in the cold.”

There was a surge of interest from around the world, Asquith said “because it was the first time a group of workers said, well, let’s devise our own alternative to the company’s corporate plan. Some people said it was like a 20th-century version of the industrial revolution!” The plan was even nominated for the Nobel peace price in 1979.

Predictably, perhaps, company managers rejected the ideas from the outset, lampooning the suggestion of wind and solar power, in one instance, as being “in the realm of the brown bread and sandals brigade”, according to a document in the film.

Asquith conceded, too, that the group never believed that the company would make their products, but emphasised that during the four years the plan was running, the company “didn’t dare declare any redundancies”.

“In the end, we got done over by the Labour government, some of the union officials and then Thatcher,” he said.

Lucas Aerospace was sold off bit by bit, and none of the eco-products was ever made. “I tell you what though, if I had my life over I wouldn’t change that Lucas experience for anything,” Asquith said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion