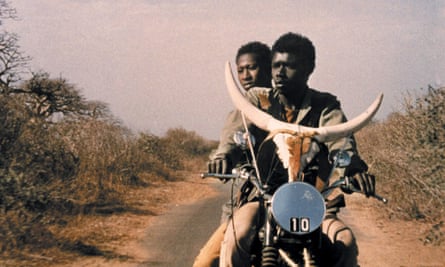

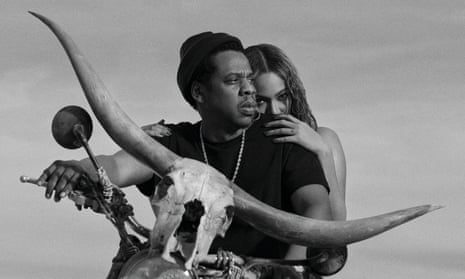

The image is arresting: a man sits astride a motorcycle, the handlebars adorned with the giant skull of a zebu, its horns forming a wide skeletal embrace. His head is turned; something beyond the frame has caught his attention. Seated behind him is a woman, her hands on his shoulders, staring straight down the lens. To some, this photograph will be instantly recognisable as a homage to Touki Bouki (the title means “The Hyena’s Journey”), generally credited as the first African avant-garde film. The fact that the couple in the modern restaging are Jay- Z and Beyoncé, with the image spearheading the promotional campaign for their On the Run II world tour, has propelled this little-known but visionary Senegalese film into the spotlight some 45 years after it was made.

Jay-Z and Beyoncé leave the UK this weekend with praise for the two-and-a-half hour stadium extravaganza ringing in their ears. In the Observer, Kitty Empire called parts of the show “unbearably exciting”, while Rachel Aroesti in the Guardian declared it “staggeringly impressive”. It’s tempting to hope that even a handful of the millions of fans who flock to the tour between now and October will investigate the film that has been one of its inspirations.

Difficult to see since its initial release in 1973, Touki Bouki re-entered circulation 10 years ago when it was restored as part of the World Cinema Project by Martin Scorsese, who called it “a cinematic poem made with a raw, wild energy”. It was filmed in Senegal for about $30,000 by the actor-turned-director Djibril Diop Mambéty and tells of the young cowherd Mory (Magaye Niang) and his student girlfriend Anta (Mareme Niang), who dream of fleeing the dusty, desperate streets of Dakar’s Colobane district for Paris. But the prospect of leaving home is a complicated one for these Africans inculcated by colonialism.

Touki Bouki was radical in resisting the social realist tradition already sweeping through African cinema in favour of a more impressionistic, herky-jerky romanticism reminiscent of Godard. “What matters here is not realism,” wrote the critic Amy Taubin when the film resurfaced briefly in New York in 1988, “but how film as one form of storytelling reveals the collective fantasy of a culture. The couple’s escape attempt might have happened, or it might have been imagined by the man, the woman or both as they lay dreaming in the sun.”

Reality, memory and daydreams flood into one another through sophisticated cross-cutting and dislocations of sound and image: the roar of Mory’s motorbike plays over a shot of cattle, while Josephine Baker sings of “Par-ee, Par-ee, Par-ee” as the camera surveys the parched rural landscape.

That song makes several crackly appearances, though each time the stylus skips back so that we never hear more than a few seconds. The song is doomed to be stuck in its groove, dreaming of better things but never quite getting there – much like Mory, who freezes on the gangplank, tormented by the memory of a cow being dragged unceremoniously to slaughter. Mambéty wasn’t the first film-maker to equate doomed humans with their bestial equivalent – Eisenstein used the analogy in his 1925 film Strike – but the colonialism that has left Mory alienated at home, yet unable to escape, gives the material a powerful new tenor.

The picture won prizes in Cannes and Moscow but was poorly received at home. “Here in Senegal, it was a big commercial flop and was taken off screen after only four days,” recalled Ben Diogaye Bèye, its assistant director. “By showing the fantasies of the youth of Colobane, Djibril also brought out their defects and they did not forgive him for that.” He didn’t direct another feature until Hyènes 19 years later in 1992. Magaye Niang attributed this extended gap to Mambéty’s perfectionism: “His aim was to make masterpieces.” The director’s own explanations tended toward the cryptic or whimsical. Shortly before his death from cancer in 1998 at the age of 53, he was questioned about his lack of productivity. “I had a love affair with a princess called Tortoise,” he said.

Though Mambéty died young, Touki Bouki has had an unusual and extended afterlife. It continues to be highly regarded, and not only by Scorsese. The black British film-maker John Akomfrah has called it “an absolute gem” and “the one indisputable masterpiece of the African avant garde.” Mambéty’s niece, the actor and film-maker Mati Diop (herself the daughter of the renowned musician Wasis Diop), directed the 2013 semi-documentary A Thousand Suns, which centres around a public screening of Touki Bouki and asks why Niang, like the character he played, never left Senegal. “Touki means ‘to travel’ and you are stuck!” his friends taunt him. “You should have travelled!” The film ends with a poignant phone conversation between him and Mareme Niang, who did make the break, like her character Anta, and now lives in Alaska.

Diop has professed herself “a little troubled” about the appropriation of Touki Bouki by Jay-Z and Beyoncé. “It looks like it’s an art director who brought them the image, and no one has been concerned about what artistic and political story is behind it,” she told Libération. “It is depressing and fascinating at the same time, the unbearable lightness of the mainstream.”

It is certainly unfortunate that the couple invoked the glories of African cinema on a tour that doesn’t call at a single country on that continent. Perhaps in the wake of their tumultuous relationship, and the references that On the Run II makes to their personal ups and downs, they were drawn merely to the incendiary nature of its vision. “Touki Bouki was conceived at the time of a very violent crisis in my life,” Mambéty once said. “I wanted to make a lot of things explode.” As Scorsese later observed: “That’s just what he did. Touki Bouki explodes one image at a time.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion