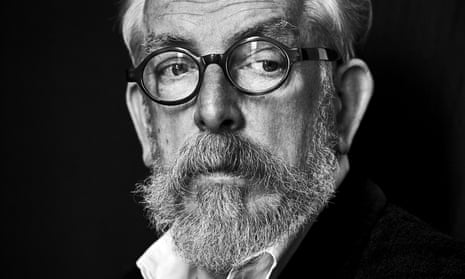

Michael Howells was a transformer of space, the key talent that unifies the different worlds he worked in: fashion, film, theatre and, of course, parties. The parties he built were literally incredible, huge replica Hitchcockian sets or dining rooms set in glass houses that slid apart after dinner to reveal a sunken nightclub below – of millions of pounds and weeks of work poured into a single fantastical night.

The first time Michael and I worked together was on my wedding. His talent was hard to define but at the time it seemed to be dressing up (he was always immaculately suited) and flowers. Michael redefined the decorative flower, no longer a stem in a box that came from the florist but anything that grew. He was a forager, so grass, trees, wildflowers, foliage, moss and weed would be twisted together and made to fly, uprooted from the earth and living for a moment in space.

A lofty (literally), imaginative, extravagant, fashionista who combined a prewar aesthetic with a daring 21st-century sensibility seemed unlikely to be contained by the disciplines of film-making with its tightly controlled world of budgets and schedules.

The film Fairytale (1997) was our first professional experience together, a story about two children who claimed to have seen something magical in a wood. While I was being hired as director, the art department had deserted to another project and I needed an immediate solution. I thought of Michael’s mastery of nature. As we stood together surveying the half-made props, Michael said, to the producer’s alarm: “Well, we obviously can’t use any of this.”

Howells’ instincts as a forager, however, meant that he preferred to find, borrow, or make rather than hire in the conventional way, and he scoured attics and jumble sales for props, then held an auction on the last day of shooting and sold everything, becoming the first art department in my experience to make a profit.

We went on to make four more films together, including Ken Branagh’s Shackleton (2002) and, most recently, Churchill’s Secret (2016) with Michael Gambon. Michael had a thrillingly meticulous eye for detail that actors loved. Shackleton’s desk on the Endurance had items in every drawer that if opened revealed something about the man; a newsroom in Fairytale had stories ready typed on every desk. As with his parties he never just built a set but always created a world for the actor to enter, in which anything was possible.

His last party was just over a year ago. He had created the Christmas decorations for Claridges and instead of a fee asked for a 60th birthday party. It was the most spectacular I have ever attended, all of us celebrating together the breadth of his talent, as a friend, a creative collaborator and a builder of extraordinary worlds.