Midnight Cowboy was the first and only X-rated film to win the Academy Award for best picture, a fact that’s useful to know on trivia night, but otherwise needs to be appended by about five or six asterisks. The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) originally rated the film an R, changed it to an X for its depiction of prostitution and homosexuality, and then changed it back to an R only two years later, a tacit acknowledgement that the board had gotten it right the first time. Seeing the film today, 50 years later, the ratings controversy seems all the more curious, given the relative timidity of its nude scenes and a gay hustle at a Times Square theater that’s all uncomfortable glances and implication.

And yet both the X rating and the best picture win tell us something about Midnight Cowboy as a watershed moment in the culture, marking a transitional period where Hollywood was responding to radical social change, but not quite keeping up the pace. It would be tempting, for example, to draw a connection between the film’s release and the Stonewall riots a month later, but it would be revisionist history to think about Midnight Cowboy as the gay rights movement gone mainstream. To the extent that Joe Buck, the film’s faux-cowboy hustler, opens himself up to trade with other men, it’s tied to desperation and shame, not the pursuit of latent desire. If he had wanted to have sex with men, the film might have kept its X.

At the same time, Midnight Cowboy is an extraordinary document of its era, as if it were the bridge to New Hollywood – accessible and sentimental in many respects, but constantly pushing the audience to accept new techniques and look to the margins of American life. Director John Schlesinger, a gay British film-maker, would push further still two years later with Sunday Bloody Sunday, a thornier and more explicit drama about sexual fluidity, but he had a keen sense of how adventurous viewers were willing to get and how far he could extend their sympathies. He made a film that could both win an Oscar and see the future that was coming around the corner.

It starts with Harry Nilsson’s rendition of Everybody’s Talkin’, which wasn’t eligible to win best original song in 1969 – and might not have, with the similar G-dropping hit Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head arriving a few months later in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid – but reinforces the film’s themes early and often. The first lines (“Everybody’s talkin’ at me / I can’t hear a word they’re sayin’ / Only the echoes of my mind”) are as concise a description of Joe Buck as possible: his stubbornness and naivety as he journeys from small-town Texas to New York City, and the “echoes” of past traumas that reverberate in his head. Jon Voight’s beautiful performance as Joe has a deer-in-the-headlights quality, but also a boundless optimism that contrasts touchingly with the hardships that confront him at every turn. He fights against a past that haunts him and fights some more against a city that’s indifferent to his cowboy kitsch and absolutely pitiless in spotting a rube in its midst.

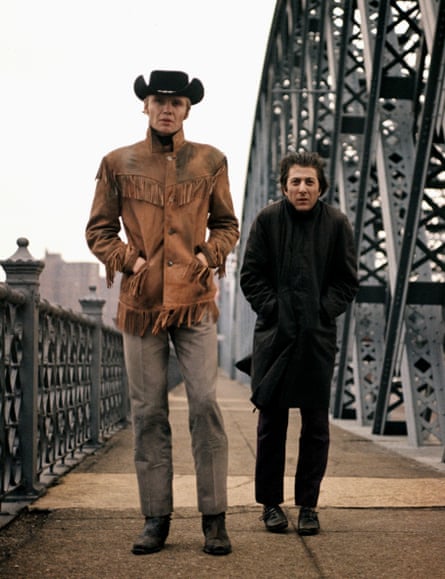

One of those rube-spotters is Enrico Salvatore “Ratso” Rizzo, played by Dustin Hoffman as a small-time conman, emphasis on “small”. The $20 he takes off Joe for setting him up with a pimp who turns out to be a religious fanatic is the biggest score he manages the whole film. The rest of the time, he’s stealing fruit or sneaking laundry into someone else’s machine or picking the occasional pocket. All the scams can afford him is a squatter’s space in a condemned building with no electricity or heat, and pipes that freeze in the winter. When Joe and Ratso meet again, the two are such partners in defeat that Joe can’t stay angry at him, and they wind up joining forces. Their team-up is like the opposite of The Avengers: their combined powerlessness gives them no defense against the world, only a little companionship.

There are several moments that haven’t left the culture in 50 years: there’s Ratso’s “I’m walking here!”, still the quintessential New York gesture; the shot of Voight bobbing in a sea of Manhattanites on the sidewalk, his 10-gallon hat not quite saving him from anonymity; and the crushing image of Joe and Ratso on the bus to Miami, with the window superimposing sunny paradise with the end of a tragic journey. Yet there’s so much more to savor about Midnight Cowboy, which seems to know that it will be one for the time capsule some day. Schlesinger has a foreigner’s eye for America, picking out images that those who live here might miss, but which crystallize his impression of its essence. He captures Texas in the shorthand of abandoned drive-ins and curio shops, and billboards that read “If You Don’t Have An Oil Well … Get One!”, and his Manhattan is a memory of 42nd Street seediness and “progress” that renders buildings into piles of rubble.

Midnight Cowboy is a fine character study of a lonely man who can’t escape the echoes of his past and even finer buddy drama about two strangers who huddle together in their unlighted corner of the world. But what really stands out in 2019 is the film’s sympathy for the marginalized, those invisible people who have no presence in the Hollywood of today, much less any political representation. Poverty is usually something to be delivered from, not something that deepens and consumes as it does here. The sad joke of Midnight Cowboy is that Joe loses money at his intended profession, lending cab money to his first trick, dropping $20 to Ratso’s scam, and getting stiffed on a movie theater blowjob before benefiting from the small mercy of a socialite opening up her wallet.

The film asked audiences to take pity on figures like him, and they did, crying at one of the great endings in cinema history and handing out Oscars for best picture, best director and Waldo Salt’s adapted screenplay. They haven’t often been asked since.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion