When Josh Howard began working on his documentary The Lavender Scare, way back in 2009, America was a very different place – not least for its LGBT citizens. Barack Obama had recently been elected president; one of his early actions, in a reversal of Bush administration policy, was to sign a UN declaration calling for the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Months later, the Matthew Shepard & James Byrd Jr Hate Crimes Prevention Act was passed. Meanwhile, the list of states to legalise same-sex marriage was steadily growing.

The prospect of a documentary about state-sanctioned LGBT discrimination, in short, seemed more like a valuable history lesson than a topical work of activism. And yet, released into the more hostile environment of Donald Trump’s America, The Lavender Scare plays rather differently. Its Eisenhower-era story of the national witch-hunt that saw scores of homosexual men and women investigated by the state, and subsequently dismissed from their jobs on the basis of their sexuality, has alarming reverberations at a time when Trump’s administration has rolled back certain workplace protections for LGBT people, when transgender people have been banned from serving in the military, and when a homophobic baker refusing to provide a wedding cake to LGBT customers can take the fight all the way to the supreme court, and win.

“I did see the lavender scare as an important historical moment that needed to be documented, but I did not anticipate that some of the messages in it would have the relevance that they do have today,” says Howard, a veteran television news producer making his directorial debut with this film. “It did take me nearly 10 years to finish this film, and I’d like to say that I was planning all along that it would have this additional resonance. But I do think it is valuable that it is coming out now, when we’re able to discuss these issues with a little bit of historical context.”

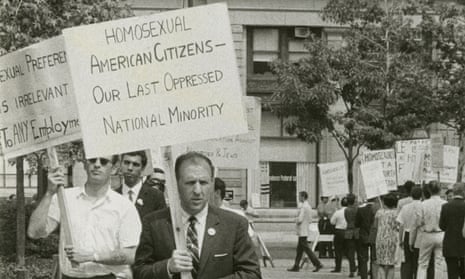

That context, meanwhile, remains relatively little known: although the lavender scare was closely allied with the anti-communist campaign led by Joseph McCarthy, it has received far less historical exposure and analysis than its red counterpart. Somewhat sheepishly, I tell Howard that prior to watching his film, I hadn’t heard of its heroic central figure Frank Kameny, a gay astronomer who, after being fired from the US army map service in 1957, devoted his life to gay rights activism, leading picket lines outside the White House in 1965. Howard in turn admits that he knew little of Kameny (or the discrimination campaign in general) before reading the historian David K Johnson’s book The Lavender Scare in 2009 – and swiftly deciding there was a film to be made from it.

“I thought I knew American history, and I’ve lived through a lot of the gay rights movement, but the idea that the government had this systematic programme of eliminating gay men and lesbian women from the workforce was something I knew nothing about,” he says. “There are few people who contributed as much to the movement as Frank Kameny did. But gay history is not taught in schools, and there hasn’t been a huge amount written about him. So I was hoping a film would help bring him the wider recognition he deserves.”

It’s a good thing Howard acted as quickly as he did, after approaching Johnson in mid-2009 with his documentary idea. The interviews with a still impassioned 85-year-old Kameny, which form the backbone of the film, were conducted in 2010; Kameny died the following year. “I realised at the outset how pivotal Frank was to the story, and he remained willing to talk to anyone and everyone about gay history and gay rights,” he says, “but there was a sense about him that he deserved recognition, or bitterness that he wasn’t more well-known. In terms of his importance, he was the Rosa Parks of the gay rights movement: a private individual who one day stood up and said, ‘I’m not going to take this anymore.’”

Kameny’s story isn’t the only one carrying The Lavender Scare, of course; following Johnson’s lead, Howard interviews a number of other gay men and lesbian women who were victimised by the campaign – only to emerge proud and triumphant in the present day, as the film details their subsequent professional and personal accomplishments. Did the film-makers seek out these happy endings from a range of different outcomes? Not exactly, Howard says. “Well, Johnson interviewed a couple of dozen people for his book, I listened to all the audio tapes, and some people were still bitter and angry and kind of broken. Yet the people I interviewed were mostly pretty optimistic and had moved on with their lives. And I always wondered if a person’s state of mind has something to do with their longevity.”

He was more surprised, however, to find several willing interviewees among the surviving men who enforced the policy, chief among them the former state department official John Hanes, whose reflections come compellingly close to a mea culpa, before he pulls curtly back to the brink. “[Hanes] said he wouldn’t do the same thing today because society has changed, but he had no apologies,” says Howard.

This turned out to be a recurring sentiment as interviews for the project continued. “Every government person we spoke to said they believed they did what needed to be done. We were surprised as we started reaching out to them for interview, because we expected them to say no. But we began to see why that was: they don’t feel remorse or embarrassment or contrition; they truly believe they were doing the right thing for the time. One of them actually said, ‘I am a patriot, and I was carrying out the orders of the president.’”

Howard is quick to insist that his first film, which brought him out of retirement, will also be his last. “It’s not that I was necessarily looking for a project,” he says, “but I came across the book, and it was just so fascinating, and it was something that people didn’t know. How could a journalist pass up that opportunity?”

Besides, as far as he’s concerned, making the film was only half the job; the rest involves trying to get it out to an unknowing public, particularly in the professional sphere that once enforced this discrimination. He’s already lined up awareness screenings at a range of corporations and law firms. How about a White House showing next? “Well, I would be thrilled,” he says after a pause. He hardly needs to say that the chances of an invitation – from the building’s current occupant, at least – look awfully slim.

The Lavender Scare will premiere in the US on PBS on 18 June with a UK date yet to be announced